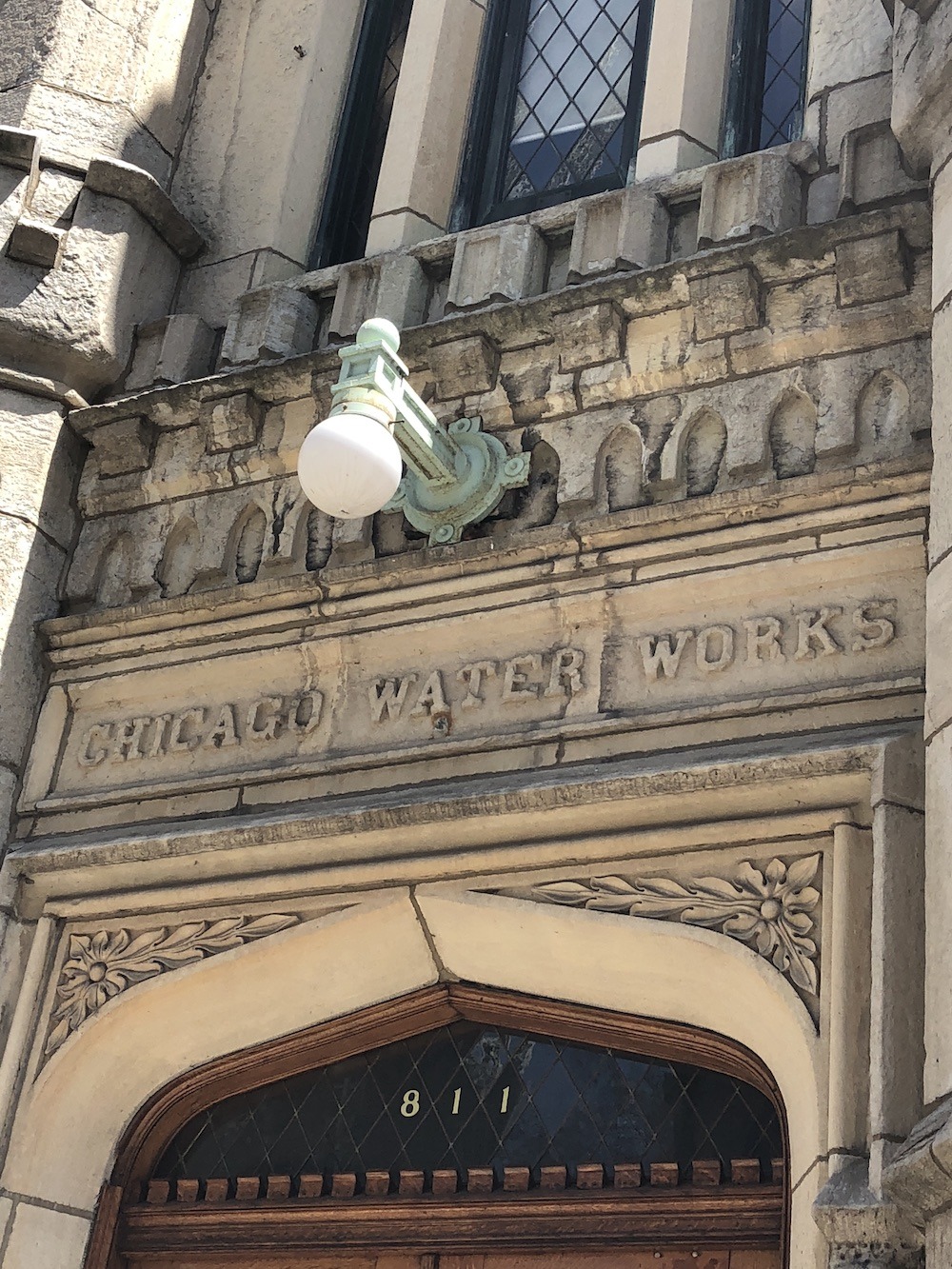

Case Study: Chicago’s Original Water Tower And Pump Station

Words: Ashley JohnsonIn Chicago 150 years ago, life was much different from what we know and experience today. Life was slower, needs were different, technology emerged in new yet different forms, and the ideals and evolution of the city differed greatly from that which we rely upon today.

At the time, one of the biggest concerns for residents of the city was sanitation. Residents drew their water from the Chicago River. Despite serving as the city’s source for fresh water, it also acted as the city’s sewer because sewage that was dumped into the river traveled into Lake Michigan. This then created a source of diseases, such as typhoid fever and dysentery.

To address the sanitation issue in Chicago and resolve the ill-effects associated with poor water quality, city planners and leaders devised a solution to draw clean water from Lake Michigan. Ellis Sylvester Chesbrough, an engineer for the city of Chicago, proposed building a new system that included a tunnel to be built sixty feet under Lake Michigan and extending two miles out from the shore. This tunnel, which was lined with two courses of brick, would then carry clean water into the city. It was completed in 1866 and in 1867 construction started for the water tower, which would equalize the pressure of the pump.

The water tower, which is the second oldest water tower in the United States and stands at 182 ft to the tip of its spire, was designed and built by William W. Boyington who was influenced by 19th century European architectural writers.

Boyington was born in Southwick, Massachusetts in 1818, and at the time was the most prestigious architects in the Midwest during the second half of the 19th century. He was trained as an engineer and architect in New York, and was known to construct schools, churches, office buildings, and railroad stations. In Chicago he built structures for the University of Chicago and the first Sherman house.

The water tower exhibits an architectural style known as “castellated gothic,” which can be seen in its battlements that act as a decorative element. In line with the nature of castellated gothic, the tower also features decorative columns, buttresses, turrets, lancet windows, and parapets. In 1882, when Oscar Wilde visited the city and saw the tower, he classified it as “a castellated monstrosity with pepper boxes stuck all over it."

Solid blocks of rough-faced Joliet Limestone that were quarried locally in Illinois, in the towns of Joliet and and Athens, which is now Lemont, were used to construct the water tower. This material was is composed of calcium magnesium carbonate and was chosen for its strength and durability. And it is recognized for its creamy yellow buff color that patinas with time and with age into a warm buttery color.

Inside the water tower is concealed a 138-foot standpipe that is three feet in diameter, and was used for fighting fires and to control water surges. The tower is divided into five sections from the ground up, diminishing in size, and consists of 168 concrete filled piles and capped with timbers made from oak that are 12 inches. Although the standpipe was removed in 1911, there still remains a spiral staircase of 237 steps inside that leads to the steel cupola at the top of a copper tower that has obtained a green patina over time.

The four corners of each of the three lower rectangular sections feature turrets that rise up, and the walls are surmounted by cut-stone battlements. The octagonal shaft from the three-tier base includes two narrow windows on each of the shaft’s eight sides at alternating heights. The outer and inner walls of the tower feature commemorations of people and events.

Similar to the water tower, the pumping station is made in the castellated gothic style using limestone quarried from Joliet, Illinois. At two stories in height, it is decorated with battlements and turrets made of cut stone and is topped with a low-pitched hipped roof. A limestone smokestack, which is smaller and less intricate than the water tower, sits on the east side of the station.

The engine room for the pumping station measured 142 ft. by 60 ft. with the ceiling rising to 36 ft. In the middle was a gallery from which operations of the engines could be viewed. The two-story central portion of the front section of the pumping station was used as drafting rooms and sleeping accommodations for engineers. The lower area contained the front entrance and engineers offices. Pumps, delivery mains and other apparatus were located below the main floor while the boiler rooms were at the back of the building. Between these two was the smokestack that rose to 131 ft.

In 1871, the great Chicago fire ripped through the city leaving only the water tower and pumping station and one other building. The water tower and pumping station was the only public building to survive. The fire destroyed the room of the pumping station and because of the severe damage, water supply to the city was cut off for eight days. The other structures to survive the Chicago fire were St. Ignatius College Prep, St. Michael’s Church in Old Town, and the Police Constable Bellinger’s Cottage.

After the Chicago fire, the use of Joliet limestone drastically declined with many builders prejudiced against the stone. Newspapers at the time of the fire reported that the stone seemed to burn like wood. So great was builders’ prejudice that they began to order brick as far away as Philadelphia.

The standpipe was removed from the water tower in 1911 and disconnected from Chicago’s water works because it became obsolete. Two restorations have been undertaken of the Water Tower. The first was when the city sought to restore the structure in 1913, but it never came to fruition. Some years later, there was consideration to have the tower moved but it was in too delicate a state. The Chicago Historical Society then worked to get the city to complete restoration of the tower, maintain it, and reroute Michigan Avenue around it. As a result, today Michigan avenue bends east of Chicago Avenue.

The second renovation took place in 1978, at which time few exterior renovations were made with the majority of renovations being taken with the water tower interior.

Today, although the tower still serves its original purpose, it now is home to the Lookingglass Theater Company, which was formed in 1988 by graduates of Northwestern University. A theater was built by Morris Architects Planners Inc., in the water tower in 2003 with a main stage that allows the theater company to reconfigure the stage and audience as needed, allowing for 240 people. A studio on the site also serves as a location for theater presentations, special events, classes, rehearsals, and small performances.

The water tower also serves as an art gallery that displays work by local artists and photographers. In mid-2000 the tower was renovated again to replace the roof by company HDR. At the same time, the Lookingglass theater was being developed by the Department of Cultural Affairs. Additionally, the general services department was working to replace the building’s facade.

At that time, the tower and pumping station was continuing its water operations while also acting as a center for tourism.

Words: Ashley Johnson

Photos: Masonry Magazine